How did the classic freeze-up of the northern Caspian Sea came to be this year? And will it continue?

After an exceptionally mild November 2023, with temperatures more than 5°C above the climatological values, an early freeze-up of the northern Caspian Sea was neither expected nor observed. December 2023 began much like November with extremely mild weather. However, winter did settle over Scandinavia and western Russia in the meantime, bringing temperatures well below freezing point and heavy snowfall to these regions. It was only a matter of time before the winds turned northwest, initiating the transport of this cold air into the region and leading to a classic freeze-up of the northern Caspian Sea.

On the 5/6th of December, a low-pressure system moved eastward across Russia and in its wake, the winds turned to northwest. Subsequently, the temperatures plummeted from +10°C to -5°C and the sea surface temperature quickly dropped from +5°C toward freezing point. Thereafter, an extensive high-pressure system (>1060hPa) settled over northern Kazakhstan, causing the winds to turn to an east-southeasterly direction and conserving the cold air in the region. The temperatures gradually dropped further to -20/-15°C and the winds increased to gale force (8Bft) with extremely low water levels over the northern Caspian Sea as a result.

Perfect combination

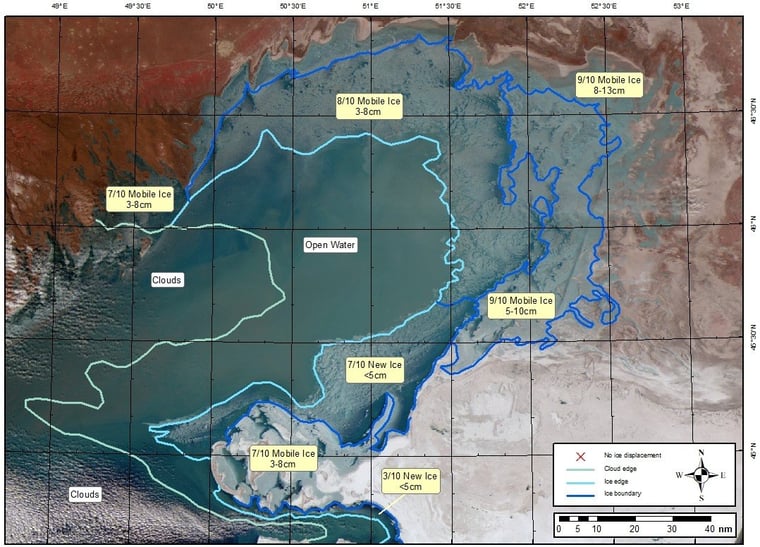

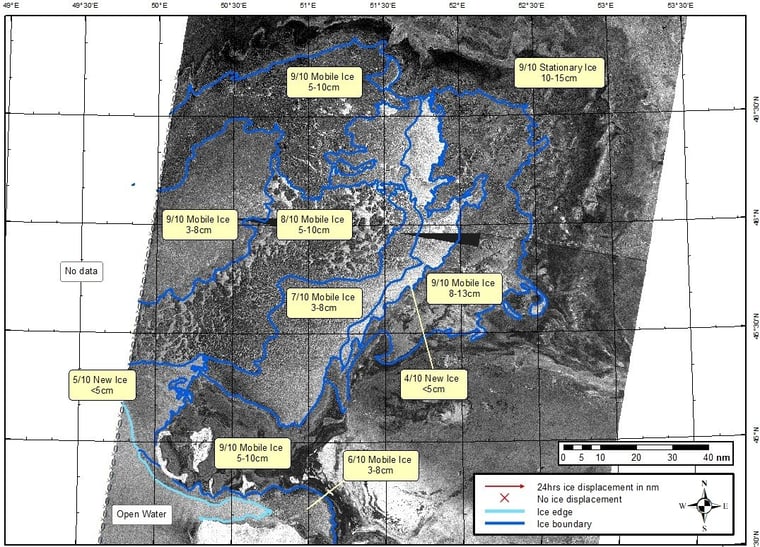

This perfect combination of temperatures well below freezing point, firm easterly winds and low water levels resulted in the rapid development of new ice over the northern Caspian Sea. Thin new ice started to develop in the wide shallow coastal zones of the northern Caspian Sea on the 7th and drifted westwards across the northern Caspian Sea thereafter. By the 12th, the shallow waters of Saddle area were closed in by new ice extending from the Volga Delta area, as well as mobile ice drifting in from the Kulaly Archipelago.

It left behind a reduced area with open water in the somewhat deeper waters of the central part of the basin, which was closed by mobile ice that drifted in from the east the following day. The complete northern Caspian Sea was covered with thin mobile ice of 5-15cm thick (Nilas of 5-10cm and Grey Ice of 10-15cm) within a week. Due to the extreme low water levels large parts of the eastern Caspian Sea felt dry, leading to restricted drift for much of the ice in the NE Caspian Sea. The Ural River, which divides Atyrau into a European part in the west and an Asian part in the east, froze over on the 10th. Picture of the frozen Ural River in Atyrau made on December 10th 2023. Photo by Lyazzat Orynbayeva.

Picture of the frozen Ural River in Atyrau made on December 10th 2023. Photo by Lyazzat Orynbayeva.

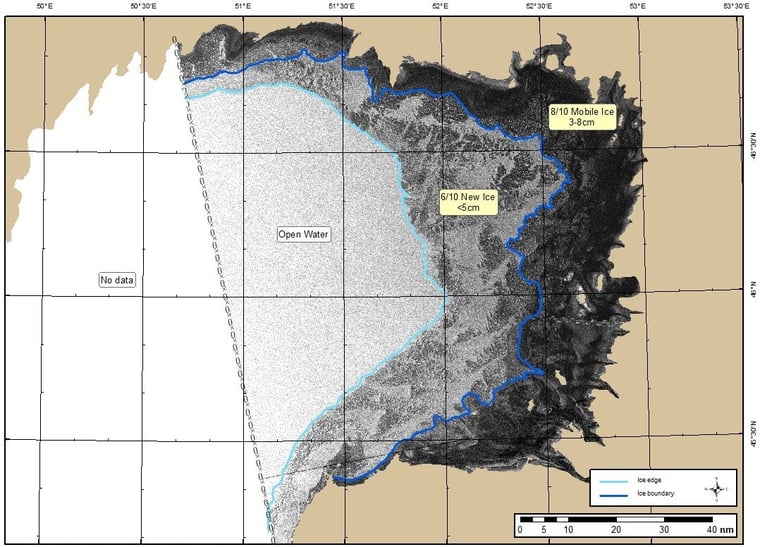

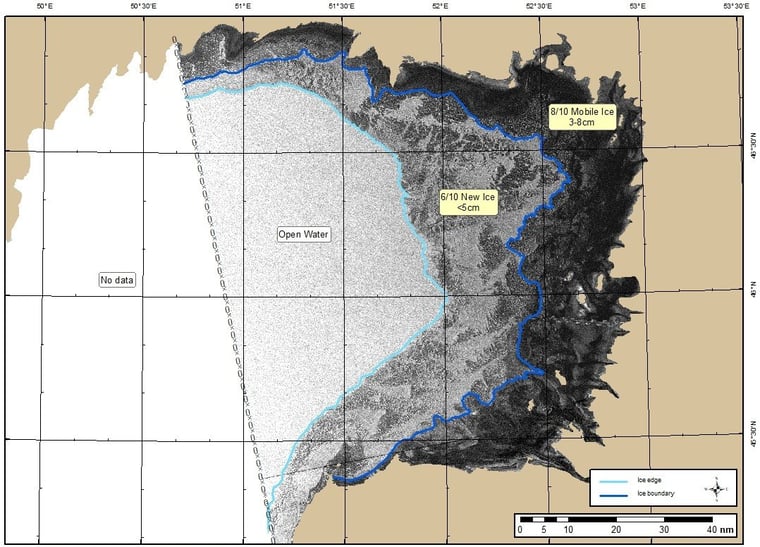

Infoplaza provides in-house ice charting services to ensure our clients can safely operate to mitigate the risk of potential ice-related hazards throughout the winter period. One of the most important products provided is the so-called Regional Annotated QuickLook, a satellite image showing polygons of ice with similar characteristics. The distinction is based on concentration, mobility and thickness of the ice. The image can also display ice drift vectors indicating recent ice movement, as well as potential ice-related hazards for vessels such as areas with grounded ice, ridges or stamukhi.

Also read: Inside the unique maritime and meteorological conditions of the Caspian Sea

The calculation of ice thickness relies on a theoretical formula that takes into account the freezing degree days (the sum of the average daily temperature below freezing point). Infoplaza frequently conducts ice thickness measurements on the Ural River to confirm these theoretical calculations once the ice is thick enough to operate safely (at least 20cm thick).

Figure 1, 2 & 3: Regional Annotated QuickLooks showing the development of the ice conditions over the northern Caspian Sea on December 9th (Radar image Sentinel-1), 11th (optical image MODIS) and 13th (Radar image Sentinel-1).

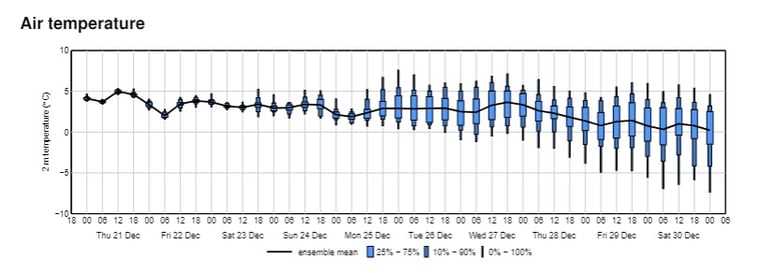

Meanwhile, the winds turned to a southwesterly direction and brought back relatively mild weather with temperatures above freezing point. This mild southwesterly flow was expected to persist till the end of the year. The combination of southwesterly winds, rising water levels bringing in warmer water from the south and positive air temperatures normally initiate melting and deterioration of ice in the southwestern part of the basin. All mobile ice then will be pushed northeast and compact towards the eastern parts of the Caspian Sea. However, the latest mid-term forecasts (see Figure 5) shows that near the end of the year the possibility of wintry weather increases again.

It’s important to note that weather forecasts are subject to change. Therefore, it’s advisable to stay updated with the latest Infoplaza weather forecasts for any potential shift in weather patterns.

Figure 4: The latest Infoplaza 10-day temperature ensemble forecast for the NE Caspian Sea, issued Thursday December 21st 2023.